SUICIDE Therapy - An Interview with James Hayes

By Krysta Gibson | New Spirit Journal

This fascinating New Spirit Journal interview with James Hayes explores a different understanding and approach to suicide: a spiritually-based therapy which helps people reconnect with their own spirit.

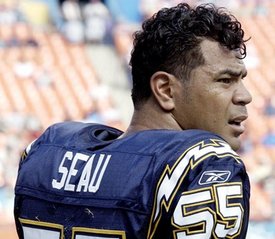

James Hayes - CCT Seattle

Suicide Therapy is is based on the work of Fredric Matteson, Suicidologist. A mental health counselor for 35 years and trained by Matteson, James Hayes explains that suicide itself is not the problem. “It is the smoke off the fire. We’re talking about someone’s answer to an unknown problem. We have to separate the smoke from the fire. We’re trying to put context to someone else’s problem. If a building is burning down and the firemen show up and they blow all the smoke out of the way and then leave, have they solved the problem?”

Many times we believe depression is the problem but he says that the issue is not always depression. We can find situations where people who were never depressed and never had any mental health problems commit suicide.

This work, he says, is ”… all based on the patient’s information and their giving this information in a context where they can understand what they’re saying. The patient speaks in codes, in metaphor. If the person listening takes it literally, then the patient is going to look pretty messed up. They are trying to tell us what the problem is and what they need but if we take that information literally then we’re going to miss what they are saying to us.”

He continues, “They have to get to a place where they can say ‘I don’t know.’ They do know the answer but need help getting there. They don’t know what they know! They’ve deceived themselves and you can’t get out of deception on your own.”

James adds “There’s an identity crisis where they do not know who they are. It’s an identity crisis where they became something they aren’t to protect something they are. They lose contact with their true self and become confident in the false self. These people are highly intelligent and they are the best manipulators in town. They manipulate themselves and then get other people to thinking there’s something wrong with them too.”

There isn’t a lot of help for this issue. If you go to the hospital, they’ll label you bi-polar, James explains. They don’t help people with a group, information, classes, or education.

The patients are the creators of this work, he says. They teach us how to help them. “I have boxes of letters thanking me. Patients thank me for saving their life. I ask, ‘How did I save your life? I was never going to kill you. I loved you from the start.’”

Suicide Therapy takes a very spiritual – not religious – approach since it is a spiritual disconnect that is the core problem. This therapy helps people reconnect with their own spirit.

A very interesting statistic James shared is that when a parent commits suicide the chances of the child commiting suicide is 56%.

To learn more about this work listen to this entire interview and visit www.suicidetherapy.com or call 206-550-3961.