Fredric Matteson has worked with 16,000 suicidal people and he has some sobering statistics: More people in the US military die from suicide than from enemy fire. Death by suicide outnumbers AIDS-related deaths, two to one. Every 15.2 minutes someone in the U.S. commits suicide. Every minute in this country somebody tries suicide.

That’s a serious issue, and yet, it’s a subject that many people don’t want to talk about.

Even talking about it in a local cafe Monday drew attention from neighboring tables. The room suddenly got quiet as the animated Matteson explained his method of treatment.

By his own account, his approach is part Robert DeNiro – “You talkin’ to me?” – and part Mother Teresa. Throw in a little Robin Williams riff and you begin to get a picture of Matteson’s high-energy approach.

“Lets’ not not talk about it,” he said. “Let’s bring some hope.”

In his 23-year career, Matteson, founder of Contextual-Conceptual Therapy, has seen a common pattern in those who contemplate or attempt suicide, and he’ll share those insights in a free two-hour talk at 7 p.m. Oct. 12 at the Commons.

“I’m trying to celebrate – not suicide, but a moment – a great moment,” he said. That moment is an opportunity to break the pattern that has kept the suicidal person in a double-bind often for most of their life.

“Suicide is a symptom,” Matteson said.

Many suicidal persons have had years of counseling, hospitalizations, and medication but say they feel better for awhile but then feel twice as suicidal the next time they are in crisis, he said. What this indicates is that an underlying problem keeps changing form but never changes.

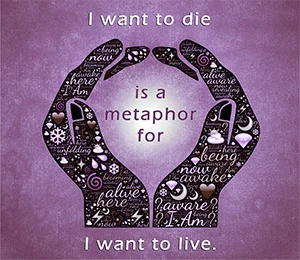

His talk, “Suicide is Not About Killing Yourself: Guiding the Suicidal Person Using Maps, Models and Metaphors,” describes the counter-intuitive approach he’s developed that doesn’t just stop the suicide attempt, but reorients the person toward true well-being.

Matteson draws on his unique experience as a poet to use “maps, models and metaphors” to help the suicidal client bypass their logic and find a way to “escape” the pain that is causing them to be suicidal.

He is sensitive to etymology that offers clues into the person’s inner terrain.

Even the word “clue” itself is loaded with significant meaning in the journey to wellness.

Matteson said “clue” came from the Latin word meaning “a ball of thread or yarn.” He connects the dots to the myth of Theseus who used a string as a guide out of the Labyrinth. The string can be followed, providing the client with more information. And it is more information that the suicidal person desperately needs, he said.

Most, he said, are highly intelligent, stubborn, sensitive people. They aren’t bad. They aren’t crazy. They simply lack very important information that will put everything they already know into new perspective.

What they need is context, he said.

Metaphorically, Matteson uses a suicidal person’s loved one as a tuning fork to recalibrate the patient, finding self-empathy “in tune with” the empathy they hold for others.

The suicidal person is locked in a high-contrast mindset of black-and-white thinking. They can spend years in a closed loop between two constructed personas – the Rock Star and the Piece of “you know what,” Matteson said.

The construct was useful at the time it was created, generally to cope with severe grief or abandonment. But it leads to a false dilemma, he said, because the person’s true identity is neither of those extremes.

Matteson uses metaphors and interactive exercises to find the solution – another word Matteson gets excited about.

It’s from the Latin word solutionem which means “a loosening or unfastening.”

The informal talk and discussion is moderated by Linda Wolf, Bainbridge Island author and founder of Teen Talking Circles and Brian C. Riedesel, Ph.D., counseling psychologist based at the American School of Professional Psychology, Associate Professor at Argosy University, Seattle and the University of Utah.

James Hayes and Jason Moran, both CCT associates, will co-present.

People who are curious about suicide; who know or work with someone who is suicidal; parents, daughters and sons, sisters and brothers, and mental health professionals are invited to attend.

For more information about Fredric Matteson and his work, visit www.contextualconceptualtherapy.com.